Mining

Friday, July 22nd, 2022 4:52 am EDT

Nicknamed the Nickel King and nickel’s Big Shot, both the bosses of Norilsk and Tsingshan have swayed the market for decades.

But now the pair’s impact on nickel trading is even more outsized, thanks to the war in Ukraine and the fallout of Xiang’s big short, which was built up on the belief his company can again transform the fundamentals of the nickel supply chain with a new source of battery grade metal.

Big shot, big short

While the physical market was digesting the possible impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine at the end of February, the March short squeeze “threatened to trigger a Lehman Brothers-like shock through the entire metals industry and possibly topple the London Metal Exchange itself,” according to one report.

After briefly sending nickel above $100,000 a tonne, Xiang walked away only $1 billion or so poorer (the position was valued around $8 billion at the time) and a chastened LME reopened trade in the devil’s copper.

The outcome wasn’t quite the Great Metal Crisis of 2022, but it was certainly more evidence that nickel could be ground zero if (or should that be when) the GMC occurs.

Too big to sanction

There are no sanctions on Russian nickel.

Canada, Australia placed sanctions on Potanin, who owns around 37% of Norilsk and is Russia’s richest man. The UK followed suit at the end of June.

Judging by the lack of market reaction to the announcements, Norilsk’s nickel appears to be flowing freely, with the price dipping below $20,000 a tonne this week for the first time this year.

Kwasi Ampofo, Head of Metals and Mining at BloombergNEF, tells MINING.COM that while Russia is responsible for around 9% of global nickel production, its output of class 1 nickel is closer to 20%. That makes it by far the biggest producer globally of nickel suitable for the battery supply chain.

“If you compare it to the current situation with gas supply in Europe, should there ever be sanctions on Russian nickel it would certainly upend the market. The prospect keeps me awake at night,” says Ampofo.

Potanin, a close ally of the Kremlin who appears to have thrived under the sanctions regime, is also making moves to stave off any restrictions on Norilsk with the opening of merger discussions with aluminium giant Rusal.

The idea being to create a company that’s “too big to sanction”. Norilsk also produces 10% of the world’s platinum and 40% of its palladium, used primarily in auto catalytic converters, while Rusal commands 6% of aluminium output. The LME banned Rusal aluminium in 2018 after the US Treasury Department imposed sanctions.

EVerything counts

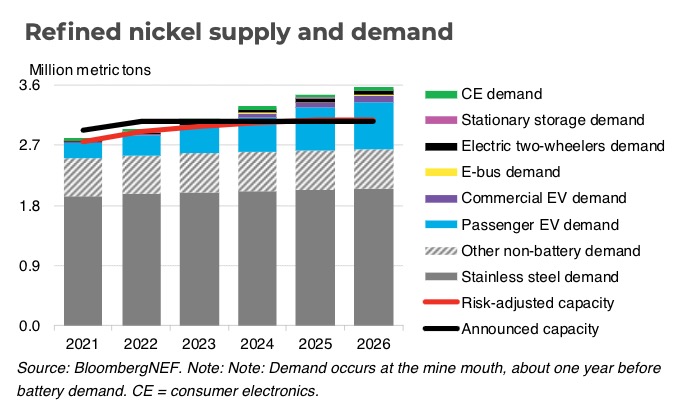

Nickel is a small market – only just over 2.2 million tonnes in 2021 – but is growing rapidly, thanks to the uptake of electric vehicles around the world. From under 400kt last year, demand for nickel sulphate used in lithium-ion batteries could hit 1 million tonnes as soon as 2026, according to BNEF’s latest outlook for the EV market.

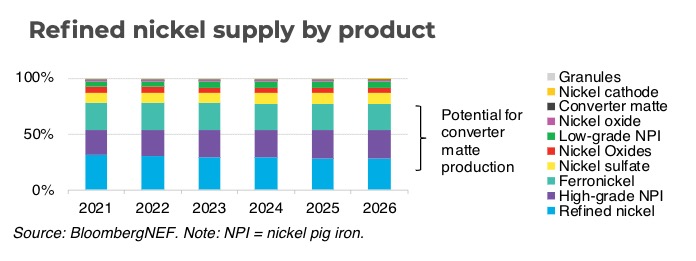

Nickel market action is concentrated in Asia, specifically Indonesia (28% of mined supply) and Philippines (15%) nickel pig iron and ferronickel trade feeding China’s stainless steel industry. China is also responsible for half the world’s nickel sulphate refining capacity.

Apart from EVs, stainless steel demand is also in a post-pandemic growth phase, says Ampofo, growing 7% this year, according to BNEF’s forecasts. Stainless steel still constitutes roughly 70% of the market for nickel.

Pals of HPAL

A slew of Chinese-backed Indonesian projects to produce Class 1 through high pressure acid leaching (HPAL) to extract nickel from low-grade laterite ores was delayed by covid-19 for the best part of two years.

Only the Obi Island HPAL project by Harita Group and Ningbo Lygend has been able to achieve commercial production, but only at the intermediate nickel level, according to BNEF.

Nevertheless, BNEF believes production of nickel sulphate in Indonesia is expected to account for 7% of the global total this year and 22% by the end of 2025 as delayed projects come on stream.

Pigging out

Another route to battery grade metal is through Tsingshan’s NPI-to-matte process, which is now beginning to hit markets in greater volumes.

Announced early last year, it was not an entirely new process, but given the company’s track record – transforming the stainless steel trade through cheap NPI – the market took the initial announcement seriously.

NPI typically contains 12%–14% nickel, ferronickel 25%–30% and matte 70%–75% which makes it suitable for sulphate production, but the process is highly energy intensive, and in many regions that energy still comes from coal-fired plants.

DSTD makes waves

Ampofo says the sustainability challenge with nickel from Indonesia is emissions and DSTD (deep sea tailings disposal).

Not surprisingly, the many mines and projects in the region using DSTD are not welcomed by environmentalists. In 2019 a spill from Metallurgical Corp of China’s Ramu operation dumped 35,000 tonnes of nickel equivalent into Papua New Guinea’s Basamuk Bay, lighting a fire under prices.

In the battery supply chain, nickel is already the worst CO2 offender, even before the circuitous route via ferronickel and NPI is taken into account.

Tesla’s impact report released in May showed 31% of the company’s battery supply chain emissions come from nickel.

Nickel imports nixed

Ampofo points out that the EU is readying regulations – the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – that imposes levies on raw material exports from countries with lax emissions policies.

That would make European carmakers reluctant to source from places like Indonesia and more dependent on Russian supply, particularly at a time when production in other parts of the world is stagnating.

And the low-carbon intensity nickel that is out there is being snapped up – just today Ford announced a a deal with BHP for nickel from its Australian operations.

Ampofo forecasts tight market conditions for nickel in 2022, with a possible technical deficit of 37,000 tonnes, in the absence of any major disruption from Russia:

“While the battery nickel coming out of Indonesia may substitute some of Russian output, global supply chains do not change overnight – that will really put pressure on prices.”

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.