Energy

Thursday, June 23rd, 2022 2:00 am EDT

For years, gas has been touted as a cheap fuel and a cheap electricity source. Perhaps not as much in today’s world, but historically, this has been the case. But not all cheap gas fired power plants are the same, and not all gas-fired power plants are as cheap to operate as proponents want us to believe.

A recent analysis from UCS studied how gas plants operated in regional wholesale electricity markets in the Midwest in 2019. This analysis looked at each week in 2019 at when power providers were operating gas plants in the regional markets MISO and SPP (covering 20 states across the central United States). It estimates how frequently power providers lost money on their gas plants on a weekly basis, creating losses that often were passed through to captive ratepayers — customers of vertically integrated investor-owned utilities, electric cooperatives, and municipal utilities — through their electricity rates.

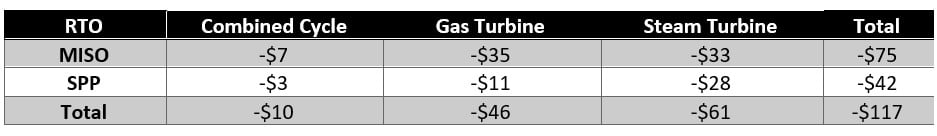

Over the course of 2019, power providers in MISO and SPP lost ratepayers $117 million from running gas plants uneconomically. Steam turbines (which occasionally are former coal plants that were converted to run on gas) and combustion turbines (which are generally used to meet peak demand) were responsible for the majority of these losses. Based on how regional markets are designed, this should not happen, especially during a year (2019) with low gas prices that would make it easier for power providers to generate inexpensive power and avoid losses. Unfortunately, there are pathways for power providers to run power plants uneconomically, and most often in the Midwest it is customers who are on the hook for the losses.

What power providers in these markets are supposed to do

Regional electricity markets (ISOs/RTOs) are designed to reduce costs for power providers and for customers. In these markets, power providers tell market operators how much electricity their power plants can generate and how much it costs to produce it. Market operators then choose the lowest-cost resources to generate until the grid’s demand is met. The power plants that run earn revenue from the market, which is meant to cover the cost of generation (if revenue exceeds that, power providers earn a profit, which can be returned to ratepayers, shareholders, or used to pay for other long-term costs at the plant). This process happens for every hour of the year and helps ensure that the lowest-cost resources are being utilized to meet demand, which benefits both power providers and customers by minimizing the costs of generating electricity.

What actually happens

Unfortunately, there are plenty of opportunities (and sometimes motivations) for power providers to skip the line and manipulate the system. While market operators are meant to dictate when power plants are operating (so that only the least expensive resources are being used), power providers have the option to run power plants when they choose, regardless of what the market operator dictates. The terminology for this behavior varies by market, but this phenomenon is generally referred to as self-scheduling and self-commitment and can lead to out-of-merit generation (in which more expensive power plants are operating in place of cheaper available resources). These designations are meant to be used sparingly, like when a plant needs to be tested, if a plant has a minimum amount of time it needs to run before it can shut down, or if a plant with a long start-up time is needed down the road for reliability purposes.

However, such designations can be exploited, causing power plants to operate uneconomically (by incurring losses), and plenty of research has shown this occurring among coal plants. One reason why power providers may operate uneconomically is to prove to regulators their plants are still useful and to continue to get cost recovery for the plant’s expenses. Another reason is to fulfill a power contract (whether that power contract is in the best interest of ratepayers is another story).

Such designations can also cater to inflexible power plants. For example, self-scheduling allows a power plant that takes up to 12 hours or more to ramp up (like most do, including gas plants) to skip to the front of the line and operate while ramping. This occasionally happens for reliability reasons, but not exclusively. That often means, however, that cheaper (and often cleaner) resources that would benefit customers sit idle or are curtailed and miss out on market revenue. Or if that inflexible gas plant is finally ramped up, and the market is no longer favorable, but the plant owner doesn’t want to cycle it all the way down, it may ramp it down partially to keep it ready for future periods, which creates customer losses by still operating when market revenues don’t support doing so.

And some power providers just don’t account for all of the costs to operate when they submit their cost to run (through their market bid). If a power provider doesn’t account for its costs properly, its resources can be called to operate in the market when the real cost to operate is higher than the market revenue it earns.

That’s a lot — but the point is, there are plenty of opportunities for power providers to operate their power plants in regional markets improperly, including at times when cheaper resources could be utilized instead. Responses may vary for why this is happening, but regardless of rhyme or reason, when it does happen and losses are incurred (especially in the Midwest), it’s captive ratepayers that are paying for it on their bills.

What we found, and what to do about it

In 2019, power providers in MISO and SPP were not consistently running gas plants economically. Steam turbines and gas turbines frequently were operated for weeks on end at a loss, and customers were paying for it. Over the course of the year, during weeks when the cost to operate was more than the revenue earned on the market (which constitutes uneconomic operation) power providers created $117 million in excessive costs, most of which were passed through to customers through their local utility’s electricity rates. The distribution of those losses can be seen in the accompanying Figure and Table.

We have a few recommendations for how this phenomenon can stop, so customers are truly paying for the lowest-cost power available:

- Regulators can do more to monitor gas plant operations. Just because a plant is running doesn’t mean it’s running economically. Conducting hourly and weekly analyses, like this, with data that isn’t available to the public, can ensure that power providers are operating their power plants in the best interest of ratepayers. Then requiring power providers to justify their operations when they appear uneconomic, and disallowing costs associated with uneconomic operations, are imperative to protect ratepayers and ensure they aren’t on the hook for unnecessarily high bills.

- Market operators can tighten up their monitoring of self-scheduling and self-commitment and report on how frequently this is occurring in their markets at a higher resolution. SPP reports on self-scheduling and self-commitment aggregated across the footprint, and MISO estimates monthly losses from uneconomic self-scheduling, but neither report at the hourly or even weekly level or by generator or owner. Doing so would help regulators with enforcement of prudent operating decisions, provide transparency for customers in how their power providers are operating power plants, and would lead to a more efficient regional system.

- Market operators and policymakers can do more to increase the flexibility of the grid and ensure that economic resources are available in the future to meet the needs of the grid. Adding more economic resources would in theory create additional supply for the grid that would reduce how frequently uneconomic gas operations occur. Both RTOs have an extensive backlog of resources waiting to connect to the grid. Almost all of these resources are clean energy resources, which are cheaper and cleaner than gas. But many of these projects have been waiting for months to years to be connected to the grid. Market operators and policymakers can find ways to reduce the barriers low-cost clean energy resources face when connecting to the grid, while bolstering transmission so that clean energy is accessible. This will undoubtedly reduce the need for expensive gas power to operate in the future and create savings for ratepayers, instead of the uneconomic costs that ratepayers pay for now.

In 2019, a year in which gas prices were at a record low, we saw evidence that gas plants were not being operated in the best interest of ratepayers. And current projections indicate that gas prices will not decrease anytime soon, putting even more pressure on the economics of gas-fired power. Policymakers, regulators, and grid operators need to do more to monitor uneconomic gas generation and reduce barriers that clean energy resources (that could replace uneconomic fossil resources) face to meet the needs of the grid. Doing so would protect ratepayers and ensure that ratepayers are not paying more on their bills than they should be.

By Ashtin Massie, energy analyst.

Originally published by Union of Concerned Scientists, The Equation.

Check out our brand new E-Bike Guide. If you’re curious about electric bikes, this is the best place to start your e-mobility journey!

Appreciate CleanTechnica’s originality and cleantech news coverage? Consider becoming a CleanTechnica Member, Supporter, Technician, or Ambassador — or a patron on Patreon.

Advertisement

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.

This post has been syndicated from a third-party source. View the original article here.